Background

Hosteen Klah (Hastiin Tłʼa, 1867–1937) was a renowned Diné (Navajo) medicine person, singer, and master weaver. Klah learned sacred chants from a young age and eventually mastered eight major ceremonials (an extraordinary number, where most singers master only one or two). After a childhood injury and healing ceremony, his family identified him as nádleehí, and he then learned the traditional art of weaving from his mother and sister. According to historical sources, Klah is believed to have been intersex (Making Queer History n.d.; Roscoe 1998; Swan-Perkins Nov. 20, 2018).

Klah’s contributions to cultural preservation were profound. In 1921, he befriended Mary Cabot Wheelwright, a Boston heiress interested in Indigenous arts. Together they founded the Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Art in Santa Fe (opened 1937), now known as the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, as a “shrine of Navajo religious beliefs.” Klah shared his songs, ceremonial knowledge, and ritual objects with Wheelwright to document Diné traditions for future generations. The museum was dedicated in his honour, with a ceremony, and to this day it stewards many of the sacred items and sandpainting tapestries he contributed (Crisosto Apache Dec. 8, 2011).

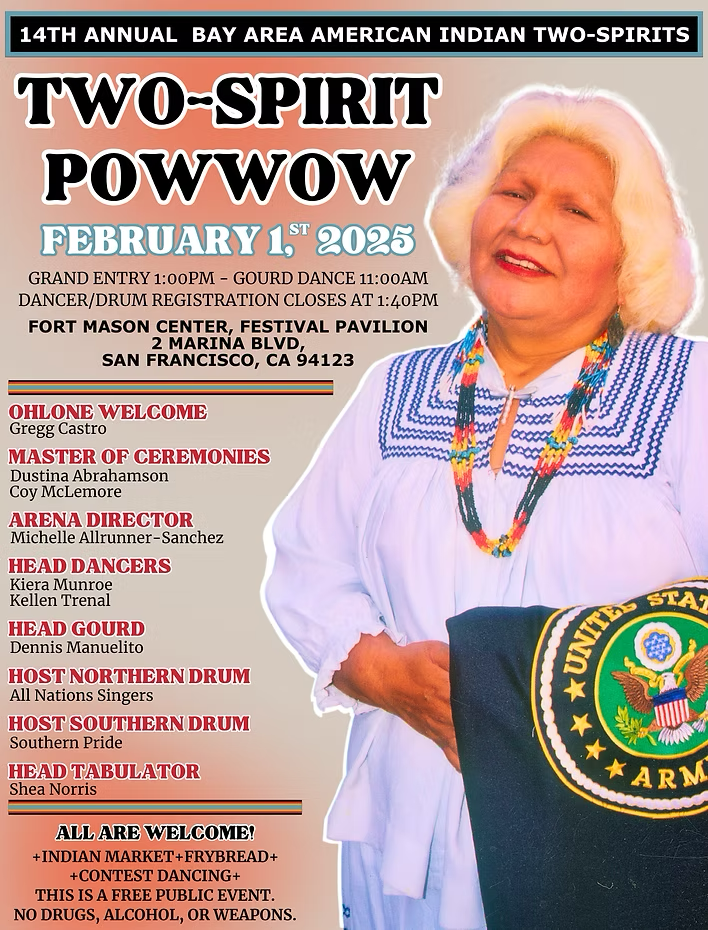

Contemporary Contexts

Navajo LGBTQ+ people often prefer the term nádleehí in their own language, but see Two-Spirit as a unifying concept across nations. Klah is frequently cited in Two-Spirit histories as a prominent Diné nádleehí who bridged male and female domains (Making Queer History n.d.; Swan-Perkins Nov. 20, 2018).

Two-Spirit and Indigenous queer perspectives emphasize aspects of Klah’s life that earlier non-Native accounts downplayed. For example, many mainstream historical sources noted that Klah never married, implying celibacy or asexuality. However, Navajo oral histories recollected in Two-Spirit narratives suggest he “had multiple partners of different genders” during his lifetime. This reframing challenges colonial assumptions about his private life and acknowledges the likelihood of rich, if discreet, queer relationships within his community. As settler public historian Amanda Timpson writes, while “most white historians” attributed Klah’s lack of marriage to either indifference or an anatomical issue, Navajo memory indicates otherwise – the physical details of his body matter less than the sacred role he embodied as a person “who embodied both a man and a woman” in society) writes, while “most white historians” attributed Klah’s lack of marriage to either indifference or an anatomical issue, Navajo memory indicates otherwise – the physical details of his body matter less than the sacred role he embodied as a person “who embodied both a man and a woman” in society (Yesterqueers, 2023).

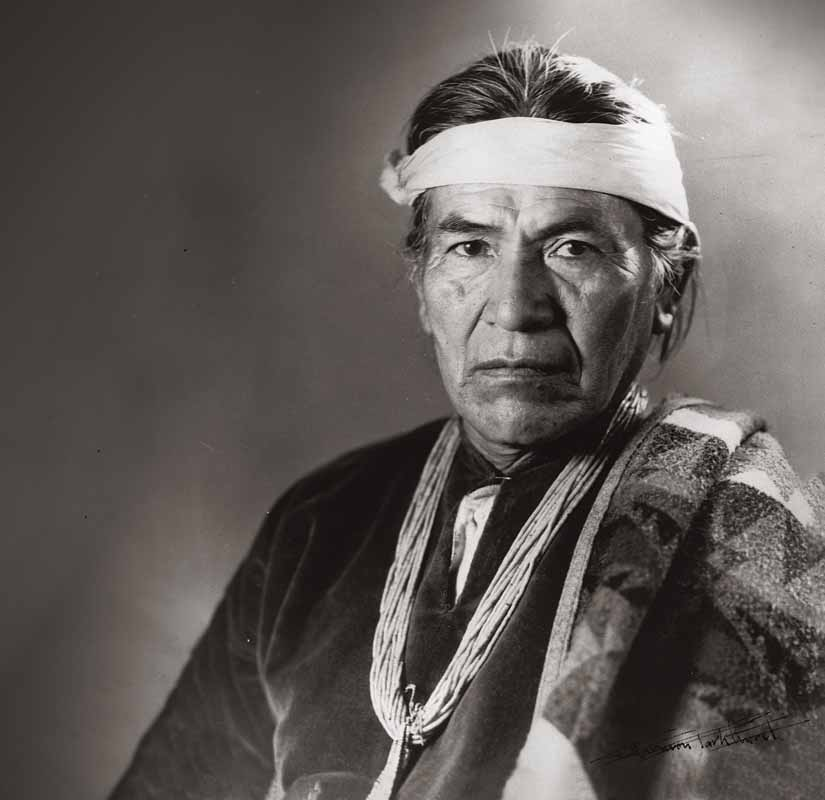

Photograph Information

Image 1 is a Portrait of Hosteen Klah, circa 1920. This is a studio-style portrait taken by T. Harmon Parkhurst, a photographer who worked extensively in New Mexico. Klah is pictured wearing a traditional headband and Navajo jewelry. The photograph is archived at the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (New Mexico History Museum) and is often used in exhibits and publications. It is considered a definitive likeness of Klah in his middle years (Image courtesy of NMHM; Neg. No. 132146, public domain due to age).

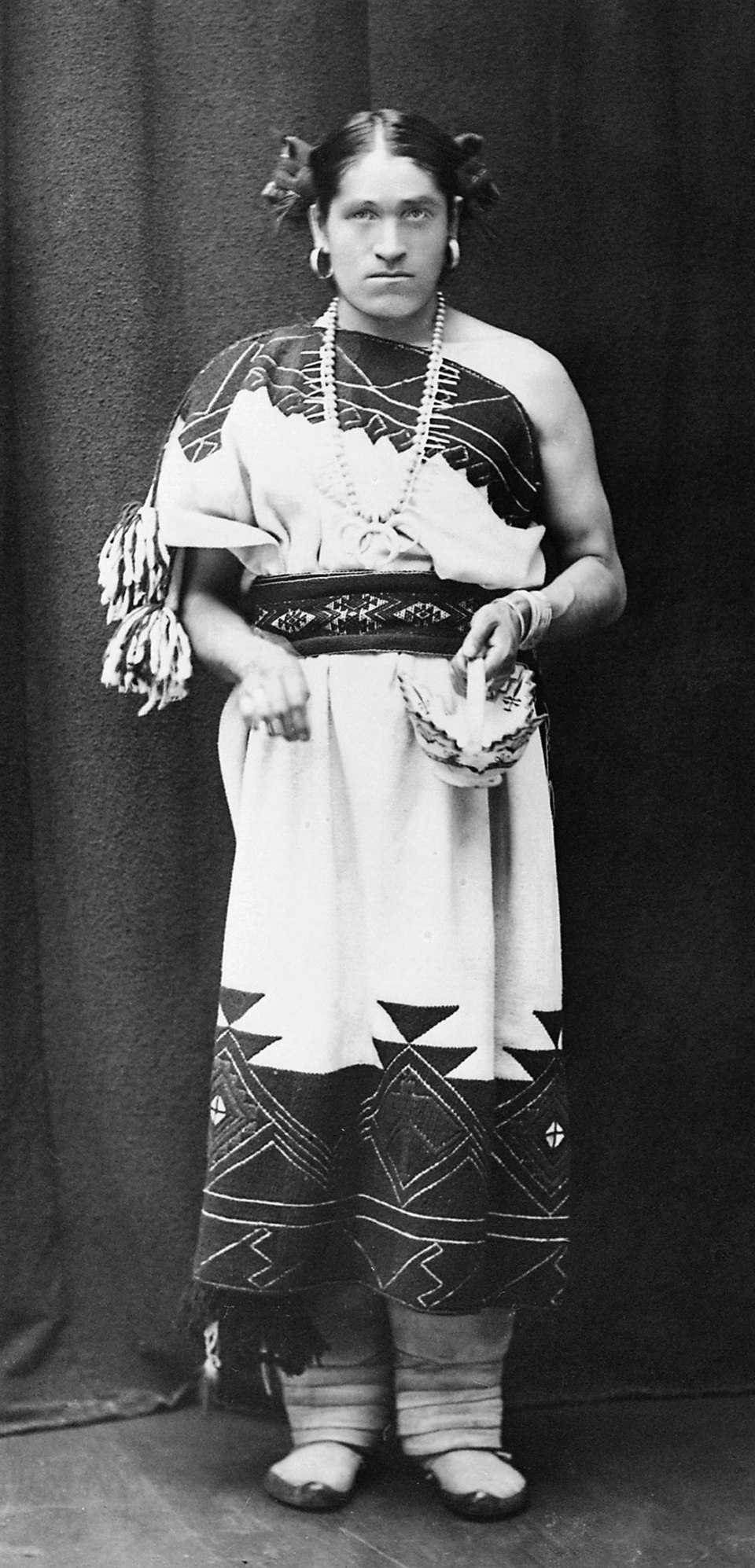

Image 2 is Hosteen Klah demonstrating a sandpainting, New Mexico, early 1930s. In this candid photograph by Franc J. Newcomb, Klah (center) is creating a ceremonial sandpainting on the ground as part of a healing ritual. Newcomb was a trader’s wife and close friend who documented many scenes of Klah’s life. This image, preserved in the Maxwell Museum archives, captures Klah in the act of performing one of his sacred duties. Such photos are rare because Navajo sandpaintings were meant to be transient; yet Klah allowed Newcomb to photograph and even helped reproduce some sandpaintings in his weavings. The Maxwell collection includes numerous other Newcomb photos: for example, Klah with family members in the 1920s, and Klah at the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair where he demonstrated Navajo culture to the public (Image from Maxwell Museum, no known copyright restrictions.)